One day, I realized, to my surprise, that Björk was a normal person who did everyday things. Few pop musicians have seemed so futuristic and so weird for as long as she has. Since the early nineteen-nineties, the Icelandic artist has charted extremes—of ecstasy and intimacy, creativity and destruction—always attuned to the possibilities emerging from dance music’s experimental communities. Everything she does feels powered by an intense, full-bodied commitment, as though animated by forces greater than anything the rest of us will ever encounter. So it was shocking when, once, I saw her quietly shopping for CDs. We know that stars are just like us. But Björk has always seemed like her own solar system.

Part of the reason Björk has stood apart is that she projects complete confidence in her own vision, whether it lights on music, politics, performance, or fashion. (Her outfits—think of the swan dress she wore, at the 2001 Academy Awards—were Internet memes before such things existed.) But the most avant-garde aspect of her work has always been her willingness to defy the conventional structures of song. Starting in the early nineties, Björk’s solo albums had a way of translating the all-night euphoria of dance music into short, riotous bursts of sound.

more here.

Some singers are born with the voices of angels, some with voices like bags of gravel. Both, I’d say, are blessed in their own way. Take the haunting, unforgettable Blind Willie Johnson, the weirdo genius Captain Beefheart, and, of course, the inimitable Tom Waits, whose mercurial persona has expressed itself as a down-and-out lounge singer, junkshop bluesman, Tin Pan Alley raconteur, Broadway showman, and more. Each iteration seems to get grittier than the last as age weathers Waits’ sandpaper voice to a rougher and rougher cut.

Waits first emerged in 1973 with Closing Time, an album Rolling Stone’s Stephen Holden described as “all-purpose lounge music… a style that evokes an aura of crushed cigarettes in seedy bars and Sinatra singing ‘One for My Baby.’” Though Waits is “more than a chip off the Randy Newman block,” Holden wrote, “he sounds like a boozier, earthier version of the same.” The description might cause some fans of Waits who discovered him ten years later with Swordfishtrombones to furrow their brows. Sure, we may always hear some Sinatra in his songwriting or delivery, but a Randy Newman-like lounge singer? A little hard to feature…. As Noel Murray notes at The Onion’s A.V. Club, “Swordfishtrombones has sounded more and more like a baseline for ‘normal’” in Waits’ oeuvre.

Although he has always drawn liberally from music of the past, in the 80s and 90s, he reached further back in time for his influences and instrumentation—into the back corners of early 20th-century outsider gospel and washtub blues, 19th-century sea shanties and murder ballads. For all his avant-garde bona fides—including his many collaborations with experimental guitarist Marc Ribot—few contemporary artists as Waits best exemplify the “old, weird America” Luc Sante describes as the “playground of God, Satan, tricksters, Puritans, confidence men, illuminati, braggarts, preachers, anonymous poets of all stripes.” Each of these at one time or another is a character Waits has played in song.

Waits’ old, weird Americana is wildly askew even for genres that prize the off-kilter. He went from making records that sound like Hollywood’s seediest corners to records that sound like drunk marching bands in machine shops. By 2004’s Real Gone, his voice modulated into a terrifying bark that commands attention and respect, yet still communicates with all the emotive power of the most angelic soprano.

You can hear Waits' transition from ironic lovelorn crooner to demonic carnival barker—and a few dozen more old, weird American characters—in the 24-hour, 380-track Spotify playlist just above. It covers Waits' entire career, from that first, 1973 album, Closing Time, and its follow-ups The Heart of Saturday Night and Nighthawks at the Diner, to Rain Dogs, Bone Machine, Blood Money, and his last studio album, Bad as Me, “a fun reminder,” Murray writes, “of Waits’ ability to be a badass when necessary.” I’d say, if you’ve heard Waits’ deep, gravelly growl at any stage of his career, you’d hardly need reminding.

Related Content:

Tom Waits Makes a List of His Top 20 Favorite Albums of All Time

Tom Waits For No One: Watch the Pioneering Animated Tom Waits Music Video from 1979

Tom Waits Sings and Tells Stories in Tom Waits: A Day in Vienna, a 1979 Austrian Film

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Stream All of Tom Wait’s Music in a 24 Hour Playlist: From 1973’s <i>Closing Time</i> to 2011’s <i>Bad as Me</i> is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

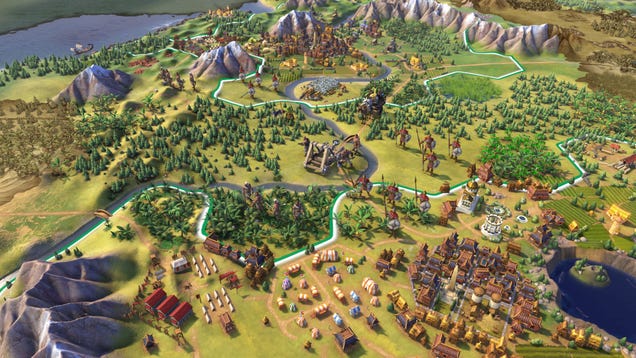

Civilization VI made some major changes in its summer update, and you can pick up the game for $30 today, the best price we’ve ever seen. Amazon lists it as the Mac version, but all you’re really buying here is a Steam code, so it’ll work on PC as well. Just be sure to place your order before Gandhi nukes the deal.

Maybe we’re just desperate for any morsel of news that doesn’t involve putting on waders and diving hip-deep into the worst of humanity, but a story in Food & Wine about the pending arrival of Kinder eggs in the U.S. has us filled with a feeling of delight akin to—well, akin to cracking open a chocolate egg and…

The movement to legalize marijuana continues to creep across the country like a cloud of smoke in a dorm room, though that buzz has been harshed somewhat by conflicts with alcohol distributors and a downtrend in pricing. But there’s one beneficiary who’s lovin’ it—McDonald’s has emerged as smokers’ preferred post-toke…